When I first began flying training, one of the first books I was issued was a big softcover text entitled Aviation Weather. It was a used book, full of dog-ears, sloppy highlights, pencil marks, and a couple of coffee stains. The illustrations in the book were black-and-white line drawings that looked like they were from the 1950s or 1960s, which seemed fitting in the beat up, musty-smelling volume. I remember it well. I used that book for the first of several college courses on the topic of aviation weather, and it was in those courses and subsequent weather studies that I learned two enduring truths about pilots. One, pilots are a rather binary bunch when it comes to learning about weather – either they find it very interesting or horribly dull (I am among the former). Two, because of our extensive study of weather, most pilots consider themselves to be something akin to amateur meteorologists.

While it might be a bit of an exaggeration to equate ourselves to meteorologists, it is true that professional pilots require a lot of working knowledge of weather in order to do our jobs. When I go to work, I have near-real time access to pretty much any weather chart/forecast/report/assessment I could conceivably want anywhere in the world, with either a few taps on my tablet or a quick phone call. However, as interesting and useful as all of this information is, a few decades of experience has taught me that one of the best tools I have is the most basic: looking out the window. And when I do, one of the best sources of information is also seemingly one of the most basic – the clouds.

Clouds tell us all kinds of things about the weather. What type they are, how high they are, how thick they are, what color they are, what shape they are, the direction and speed of their movement, if they are producing virga or rain or lightning or ice or snow or hail or wind shear or microbursts – all of these things have meaning for pilots making decisions on how to best conduct their flights in, around, under, and over the prevailing weather. We can tell you a lot about a cloud, and likely what the weather around it is like, just by looking at it. For me, it’s like my brain has a little cloud Rolodex, ready to spin to the standing lenticular or cumulonimbus or cirrostratus card whenever I might need it. It has served me pretty well over the years.

As helpful as it is, I’ve noticed a bit of a downside to my little brain-cloud-database. I can remember times in the past, for example, when my son has pointed at a cloud and said “look dad, that one looks like a doggy!” I didn’t see a doggy. I saw a towering cumulonimbus cloud that might produce lightning, hail, and severe turbulence. I should avoid it in flight by twenty miles on the upwind side, and not attempt to go over or under it. Sigh. Sometimes, I thought to myself, I wish I could just see a doggy.

In the past year or so, though, an interesting thing happened as I worked my way through a few little art courses. Anytime I tried to draw a cloud, I just wasn’t happy with the result. Why was this so difficult? A little poofy cloud shouldn’t be so hard, right? Especially when I’m constantly surrounded by clouds. Was I being too hard on myself? Probably. Besides that, though, I realized something; at some point, I had become so focused on analyzing the clouds that I stopped looking at them. They were merely objects to be scanned, reacted to and dismissed, rather than appreciated as unique and often beautiful formations with infinite variations in size, color, shape, and depth. If I wanted to change the way my clouds looked on paper, I needed to change the way I looked at them.

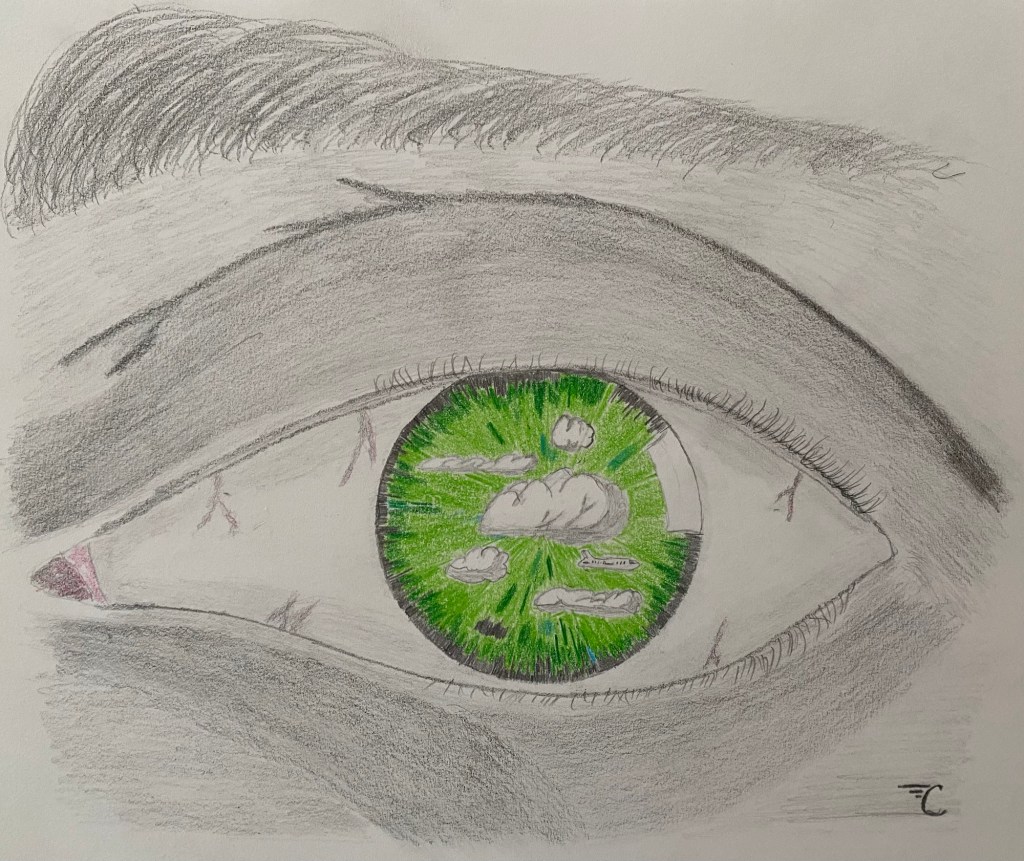

And so I did. How? By sitting with a sketch pad, and again using the tool so useful for aviators – looking out the window. Gradually, I saw more of the details of the clouds, and as I did, the same nuances started to appear in my little sketches. Throughout this process, I often thought of the ancient Greek understanding of vision, where they believed that human vision began in the center of the body and emanated out of the eyes like beams. We know now that this is physiologically inaccurate, but this understanding does perhaps seem to be a helpful analogy for understanding how we perceive the world as humans. The biological process of seeing is well understood, but somewhere between stimulus and response, our minds shape and interpret what we see in all kinds of ways that we may not even be aware of. For me, it required putting the clouds into a different context (the context of creating art) to see how narrowly my mind had been viewing them – as a barrier to completing a task that I was charged with. Which was not a bad thing, but certainly had room for growth in such a simple thing as appreciating the beauty of the clouds.

On my most recent flying trip, my first officer and I took off out of Tampa Bay, Florida, bound for Dallas, Texas. It just so happened that on this day, a wide band of late winter thunderstorms stretched across most of Florida, from around Pensacola to Daytona Beach. Because of this, we had to change our route a little bit to circumvent some of the big storm cells. So, we analyzed our weather radar, talked to air traffic control, and of course, looked out the window to help plot the best course around the weather. As we made our routing decision and turned to the west, I noticed that the biggest of the storm cells I could see looked kind of like a poodle with a top hat on. That made me happy.

AB25