A couple of years ago, I picked up an on again/off again hobby of pencil drawing. This was, for me, a departure from anything I had done in the past. I’ve been a guitar player for many years, and I’ve dabbled in other instruments here and there. I do have a little musical aptitude, as long as you don’t ask me to sing. It’s not pretty. Trust me. But I digress. Back to the topic at hand – I’d never really done much around visual arts as an adult, with the exception of a photography class a few years ago, which I enjoyed very much. When I decided to give drawing a try, I did it because it seemed like an interesting way to stretch my mind in a no-pressure way. If the results were terrible or I hated doing it, I wasn’t out anything other than the cost of a pencil, a sketch pad, and a little time. And who knew, there are a few talented artists in my family, so maybe I had some aptitude that I wasn’t aware of.

So, having duly equipped myself with pencils, a sketch pad, and a book of drawing lessons, off I went. As I worked my way through a handful of lessons, I did my best to do what my book was suggesting, that is, allowing my mind to shift from its usual analytical/logical mode to one that was more creative and abstract. This was (and still often is) easier said than done; it took time, and it shined a white-hot spotlight on things that easily distracted my brain, which sometimes feels like a rapid-fire bag of highly caffeinated and attention deficient cats….(I want a drink. Maybe a snack too. Did I leave the iron on? What about the stovetop? I like cake. I think I have to pee. What time is it? What movies has Pedro Pascal been in? Does my truck need an oil change? What time does the baseball game start? Do I have eggs for tomorrow? Remember that mean thing that someone said to you when you were 12? And on and on….)

Faced with these mental barriers, I realized that part of the challenge was that my mind was being so noisy not only just because that’s its usual way of being (it often is), but also because it was actively resisting this shift to a quiet and artistic mode – it didn’t want to. It didn’t want to because it was different, and because it was different, it was difficult, so it was trying anything to move back to what was normal and comfortable. Any mode of distraction would do, as long as we could stop with this drawing silliness. Challenge accepted, I thought to myself, and I persisted in drawing Spider-man, then a chair, then a pumpkin, then a fish. The noise persisted, and I also persisted, not allowing myself to stop until the task of the day was finished, despite the many and varied protests of my vexed brain.

Then, it happened. One day, in the middle of yet another drawing exercise, the noise vanished. Left in its place was something like a vision, but it wasn’t – more like a gentle impression. My brain finally let go, and connected me to other things I had done – highly demanding acrobatic flight in the F-16, riding a motorcycle through the European mountains, playing music in the flow with my eyes closed, and others – things that were done not by logic or analysis, but by what I saw, heard, and felt. It was at that moment that I realized that drawing was not about motor skills, pencil weights and shading techniques – it was about sight. It was about drawing what I saw – not a hand or a fish or a vase, instead, a shape, a line, a gentle curve, a depth of field, a fading of light to dark and back to light again. After that, a cascade of other things came to light as I drew more: I noticed more detail in everyday objects – light, shade, texture, and the relationship to the negative space around them. Furthermore, even the most ordinary of objects that I never paid much attention to became deeply interesting – a chair, a table, a doorway, a coffee mug; everyday things became objects of great interest as I studied the nuances of their materials, shapes, shading and contours.

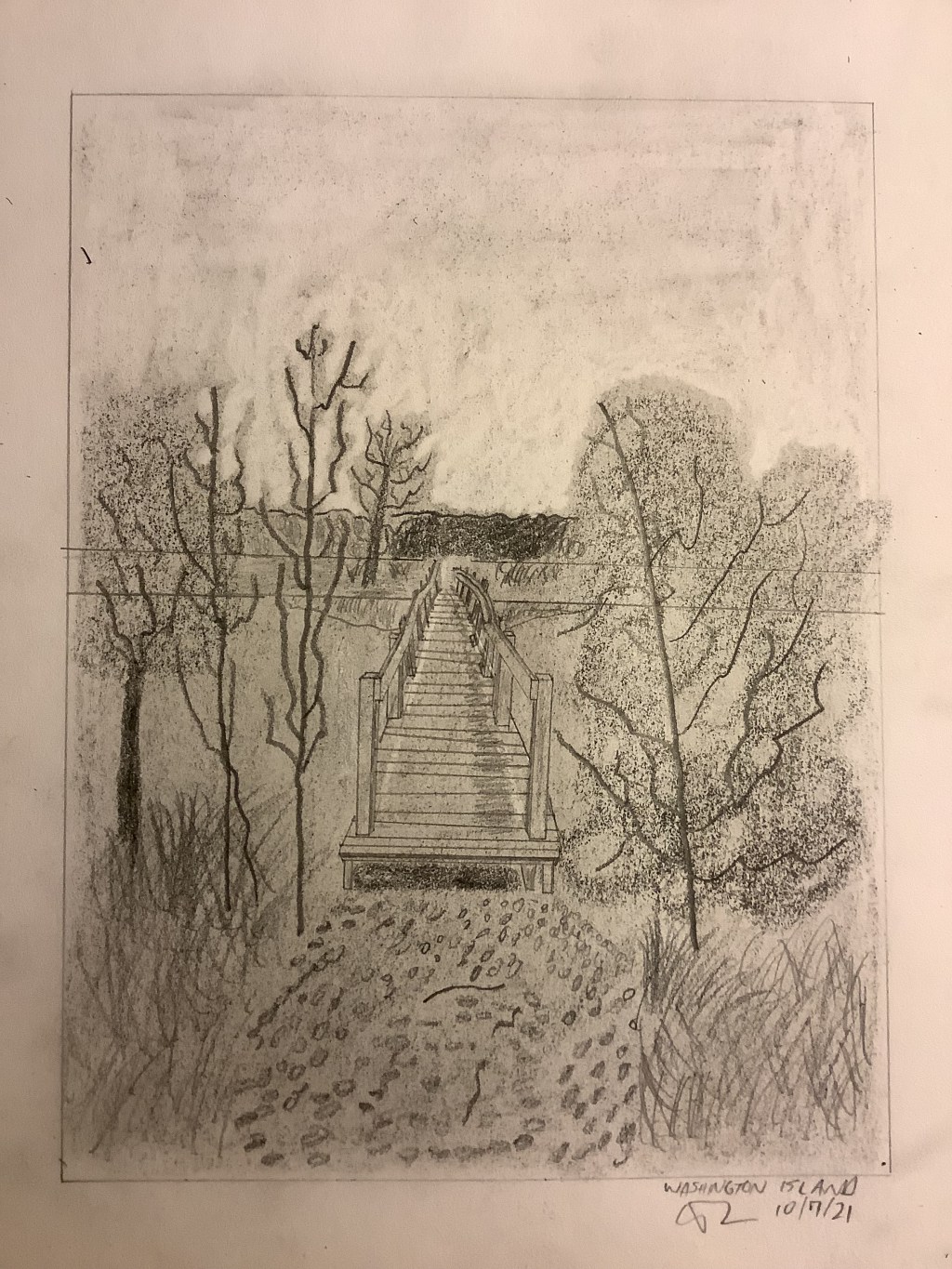

It’s not like I suddenly became a great artist when this mental shift happened; I often get frustrated with the quality of my results. Great art does take time, talent, and many years of practice. Motor skills, pencil weights, shading, and other skills do matter a great deal in the quality of a drawing. And so, I continue to draw, with the hope that the quality of my drawings will improve over time. At the same time, that’s kind of not the point. To me, the real lesson of drawing is that there is great wisdom in pushing our brains out of their normal patterns from time to time – facilitating different ways of thinking and seeing, whether that is through art or some other means. I didn’t fully realize how regimented my mind could be, and how hard it would resist departing its preferred mode of being, until I pushed it to do something different. I wonder, then, are there lessons in that for how I view the world? For my opinions on social and political issues? For my views on parenting, work, and marriage? I think there are many. Perhaps I can use the lessons of the drawing pad to cultivate a more agile mind that can look at the world and those I interact with in a different way, or at the least, show me ways in which I could think in a better and less regimented way – ways that will make me a better pilot, husband, dad, and human.

This is why I draw. Now, where’s my pencil?

AB2